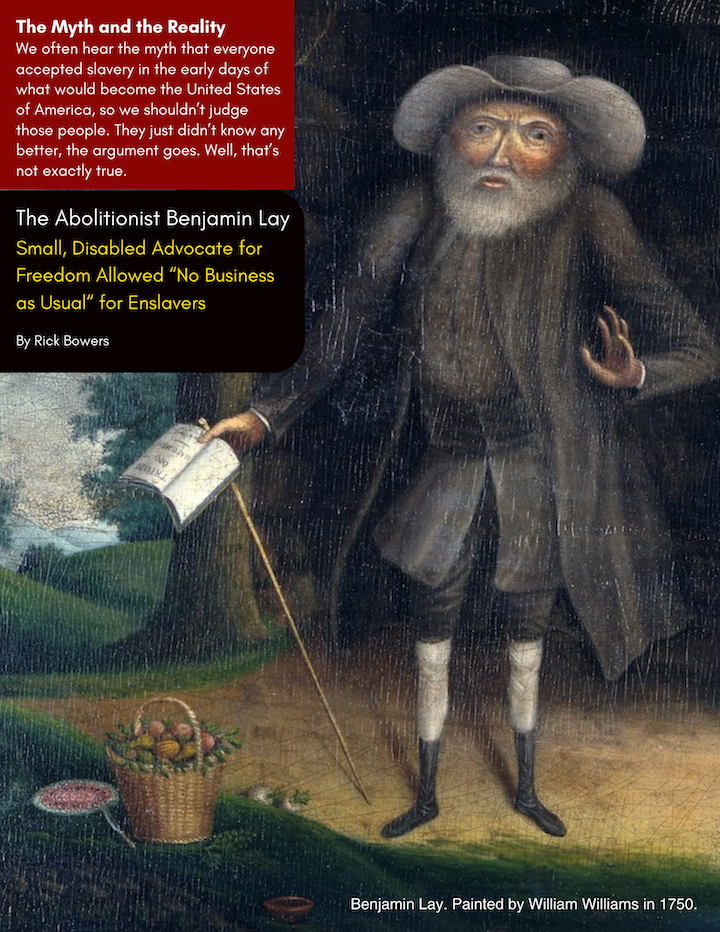

The Abolitionist Benjamin Lay: Small, Disabled Advocate for Freedom Allowed “No Business as Usual” for Enslavers

It’s not the physical size of a man that makes him truly mighty. Just ask Goliath

who was killed by David, who was much smaller than him.

Neither is a “perfectly formed” body a requirement for being strong.

Although he was only about 4-feet tall and had a malformed body with a curved

spine, very slender legs, and a large head, Benjamin Lay stood strong and firm

against slavery, cruelty and injustice in the 18th century when many considered it

normal to mistreat and cruelly abuse other human beings. Lay—a “little person,”

or dwarf—believed that all people were equal and that slavery needed to be

brought crashing down. Though small in stature, he was a giant among his peers.

Standing Tall Against All

According to a story from Isaac Hopper, a 19th century Quaker and abolitionist, Lay, who lived from 1682 to 1759 gave no peace to slaveholders. During Quaker meetings, if a slaveholder spoke during the meeting, Lay would shout out, “There’s another negro-master!”

Born in England to Quaker parents, Lay started out as a shepherd and then became a glover before becoming a sailor when he was 21. While working in Barbados as a shopkeeper, he watched an enslaved man who was unwilling to be whipped again kill himself to avoid punishment. Such incidents made him uncompromising against slavery.

After coming to Philadelphia and taking up residence there, he began speaking out, writing and protesting against slavery, putting him against the established church. As a devout Quaker, he felt that the slavery was incompatible with the Quaker religion, and it angered him that many Quakers of the time, including community leaders, were slaveowners.

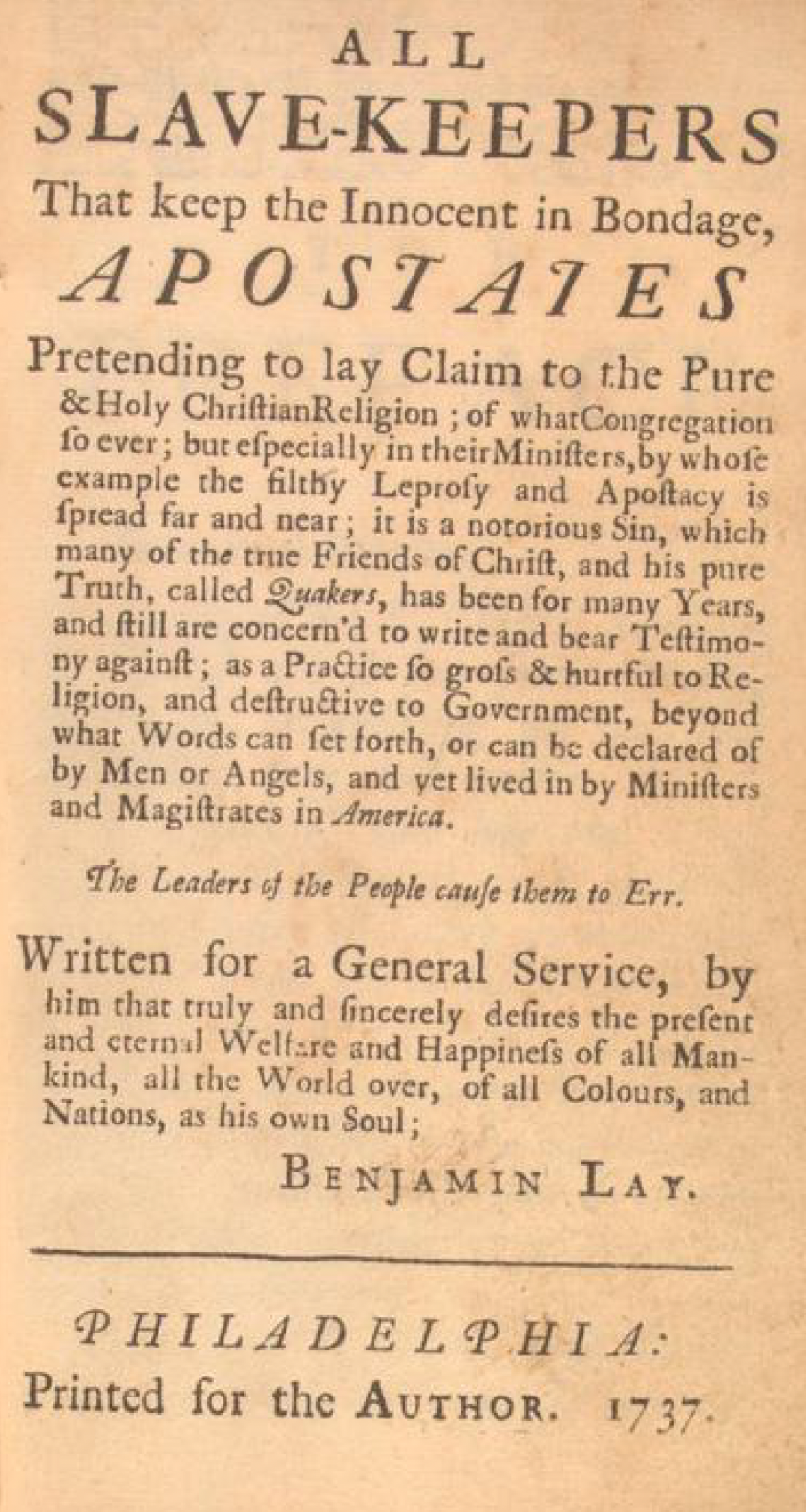

Published in 1737 by his friend and renowned early

American leader Benjamin Franklin, Lay’s most famous pamphlet was All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates, in which he attacked slaveholders and advocated for the abolition of slavery. He said that it was the duty of all Christians to fight against it. His widely read—but controversial—pamphlets proclaimed the evils of slavery and give lie to the excuse of some that slavery was simply accepted by all in those days.

“There was a time when the name of this

celebrated Christian Philosopher … was familiar to

every man, woman, and to nearly every child, in

Pennsylvania,” according to Benjamin Rush, a

leader of his time and one of the signers of the

Declaration of Independence.

Despite the opposition of many Quakers who

were angered by his attacks, Lay continued to

publish his pamphlets until he died.

During religious meetings of various churches,

he would often interrupt services to advocate

against slavery. In 1738, at the yearly meeting of

Quakers in Philadelphia, he took with him a

hollowed-out book in which he had placed a

bladder with red liquid. At one point, he stood up

to protest against the hypocrisy of the Quakers

and stabbed the bladder with a sword as if spilling

blood on some of the attendees. He noted that

while their religion espoused equality, many of

them were slaveholders and would suffer

punishment.

Considering him a troublemaker and a threat to their faith, the community expelled him. And it was not the first time he’d been expelled from church. He had also been expelled from congregations in England.

No Compromise With Slaveholders

Lay refused to participate in slavery or to deal

amicably with those who did. He was once invited

to have breakfast with an “important” person of the

community and his family, but when Lay saw a

black man coming to serve them, he said to the

man who’d invited him, “Dost thou keep any

Negro slaves in thy family?” Upon hearing that he

did, Lay announced that he would not eat with

them and partake “of the fruits” of unrighteousness before walking out. He was one of the first people who boycotted products that were made by slaves.

He and his wife, who was also a “little person,” made their home in a cave in Pennsylvania in 1739 and lived there for many years until about 1748 when he then moved into a small house. He wanted to live simply

and protest materialism and the excesses of

the wealthy. While living in his simple home, he

made his own clothes and grew his own food.

While some people considered him too extreme

and criticized him, Lay did not back down. For him, those who were cruel to their fellow human beings should not expect to simply enjoy “business as usual.”

Standing strong against all criticism and

staying firm in his convictions, Lay also became

an inspiration to other abolitionists such as the

great leaders William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick

Douglass, and John Brown—men whose

activities were largely responsible for the

ending of slavery in the United States. He is

now a symbol of the strength of one person’s

action to overcome injustice—regardless of our

physical bodies or disabilities. Lay’s life shines

a light on an important truth: Our hearts are

much more important than our bodies, and a

big heart makes a big person.

For More Information

The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf Who Became the First

Revolutionary Abolitionist (2017)

Prophet Against Slavery (2022)